Contents

Depression is one of the most common mental health challenges worldwide, affecting more than 280 million people globally (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). Symptoms range from persistent sadness and fatigue to impaired concentration, loss of motivation, and in severe cases, suicidal ideation.

Traditional treatments, such as antidepressant medications and psychotherapy, remain crucial. However, growing scientific evidence highlights another effective tool: exercise.

Over the past two decades, hundreds of studies and systematic reviews have shown that physical activity can reduce depressive symptoms, prevent relapse, and even rival the effectiveness of antidepressant medication in some cases (Cooney et al., 2023; Schuch et al., 2020).

In this article, we’ll take a deep dive into the science of exercise and depression, covering:

- Neurochemical changes and brain mechanisms

- Stress, inflammation, and immune regulation

- Psychological and behavioral pathways

- Evidence from clinical trials and meta-analyses

- Practical recommendations on exercise types and duration

- Limitations and considerations

1Neurochemical Changes: Exercise as a Natural Antidepressant

One of the strongest explanations for the antidepressant effects of exercise lies in neurochemistry. Depression is often associated with deficiencies in neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, as well as impaired neural plasticity. Exercise directly addresses these.

1. Endorphins

Exercise triggers the release of endorphins, sometimes called the body’s “natural painkillers.” These peptides not only reduce physical discomfort but also induce feelings of euphoria, often referred to as the “runner’s high.”

2. Serotonin and Dopamine

Physical activity increases serotonin synthesis and turnover in the brain. Serotonin is critical for mood regulation and is the main target of SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), one of the most prescribed antidepressants.

Similarly, dopamine pathways—associated with motivation and pleasure—are enhanced by exercise. This is particularly important since dopamine dysfunction is strongly linked with anhedonia (loss of pleasure), a core symptom of depression.

3. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF)

Perhaps the most fascinating finding is exercise’s impact on BDNF, a protein that promotes neuronal growth and plasticity. Patients with depression often have reduced BDNF levels, leading to impaired brain connectivity, particularly in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Zhang et al., 2022).

- Aerobic and resistance exercise both increase BDNF.

- A single bout of moderate exercise can raise BDNF levels temporarily, while long-term training induces sustained increases.

This suggests exercise doesn’t just change how the brain functions—it changes its structure and resilience.

Stress, Cortisol, and Inflammation

Depression is not just a brain disorder—it’s a whole-body condition, linked to chronic stress and systemic inflammation.

1. Cortisol Regulation

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, is often elevated in depression. High cortisol damages the hippocampus, interferes with memory, and worsens mood. Exercise helps regulate cortisol by:

- Lowering baseline levels over time

- Improving the body’s resilience to stressors

- Enhancing parasympathetic (calming) nervous system activity

2. Inflammation and Immune Function

Numerous studies have found that people with depression often have elevated inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Chronic inflammation can impair neurotransmitter function and worsen depressive symptoms.

Exercise acts as an anti-inflammatory intervention, reducing CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor alpha). This dual effect—reducing stress hormones and inflammation—may be one of the strongest biological reasons why exercise improves mood (Schuch et al., 2020).

Psychological and Behavioral Pathways

Beyond biology, exercise combats depression through psychological and lifestyle-related changes.

1. Behavioral Activation

One of the most effective therapies for depression is behavioral activation—encouraging individuals to engage in structured activities despite low motivation. Exercise is a natural form of this therapy. Even small workouts provide:

- A sense of achievement

- Disruption of negative thought cycles

- Increased daily structure and routine

2. Improved Sleep

Sleep disturbances are both a cause and symptom of depression. Regular exercise:

- Increases slow-wave (deep) sleep

- Improves sleep onset and efficiency

- Regulates circadian rhythms

This creates a positive feedback loop: better sleep → improved mood → more energy for activity.

3. Self-Efficacy and Mastery

Depression often erodes confidence and self-worth. Exercise provides measurable progress—whether it’s lifting heavier weights, running farther, or simply completing a daily walk. These small wins reinforce self-efficacy, which is a psychological buffer against depression.

Evidence from Clinical Trials

The claim that “exercise helps depression” isn’t just anecdotal—it’s supported by large-scale clinical studies.

1. Randomized Controlled Trials

- Blumenthal et al. (2007): Compared aerobic exercise, sertraline (an SSRI), and a combination of both in older adults with major depression. Results showed exercise was as effective as medication after 16 weeks.

- Dunn et al. (2005): Found a clear dose-response relationship—higher amounts of exercise led to greater reductions in depressive symptoms.

2. Meta-Analyses

- Cochrane Review (Cooney et al., 2023): Analyzed 39 trials involving over 2,000 participants. Concluded that exercise has a moderate to large effect on reducing depression.

- JAMA Psychiatry Meta-analysis (Schuch et al., 2020): Confirmed that physical activity reduces the risk of developing depression and helps treat existing cases, regardless of age or gender.

How Much and What Type of Exercise?

1. Duration and Frequency

- 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity exercise (e.g., brisk walking) is the most evidence-based guideline.

- Benefits can occur with as little as 30 minutes, 3 times per week.

- Even 10–15 minutes daily provides measurable improvements in mood.

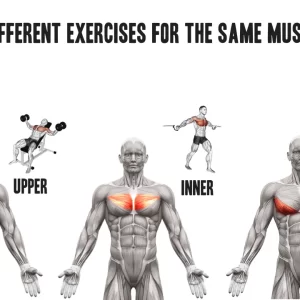

2. Aerobic vs Resistance Training

- Aerobic exercise (running, swimming, cycling) shows strong effects on mood and stress reduction.

- Resistance training (weightlifting, bodyweight exercises) also improves depression, especially self-esteem and cognitive function.

- Combination programs may provide the best overall benefits.

3. Group vs Individual Exercise

- Group exercise adds social support, reducing isolation.

- Individual exercise helps build self-reliance and flexibility.

- Both are effective, and choice depends on personal preference.

Limitations and Considerations

While exercise is powerful, it is not a cure-all. Important considerations include:

- Severity of depression: In severe cases, motivation may be too low to initiate exercise without professional support.

- Accessibility: Not all individuals have safe spaces, resources, or physical health to engage in vigorous activity.

- Adherence: Drop-out rates can be high without structured programs or guidance.

This is why many researchers recommend exercise as an adjunct therapy, not a sole replacement for medication or psychotherapy, especially in moderate-to-severe depression.

Conclusion

The evidence is clear and compelling: exercise is an effective, scientifically validated tool against depression. By:

- Boosting serotonin, dopamine, and BDNF

- Reducing cortisol and inflammation

- Enhancing sleep, confidence, and daily structure

…exercise provides both biological and psychological resilience.

It may not replace traditional treatments in all cases, but as a low-cost, accessible, side-effect–free intervention, physical activity should be considered a first-line strategy in mental health care.

Practical takeaway: Even 20–30 minutes of brisk walking, cycling, or resistance training most days can significantly improve mood and reduce depressive symptoms.

References

- Blumenthal, J. A., Babyak, M. A., Moore, K. A., Craighead, W. E., Herman, S., Khatri, P., … Krishnan, K. R. (2007). Effects of exercise training on older patients with major depression. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167(8), 797–804.

- Cooney, G., Dwan, K., Greig, C., Lawlor, D., Rimer, J., Waugh, F., … Mead, G. (2023). Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1), CD004366.

- Dunn, A. L., Trivedi, M. H., Kampert, J. B., Clark, C. G., & Chambliss, H. O. (2005). Exercise treatment for depression: Efficacy and dose response. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.09.003

- Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., Silva, E. S., … Stubbs, B. (2020). Physical activity and incident depression: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(4), 361–369.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- Zhang, Y., Liu, L., Peng, Y., & Wu, K. (2022). Exercise and brain-derived neurotrophic factor: Implications for depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 821228.