Contents

- What Is the Balance Beam Walk?

- Muscles Worked

- Balance Mechanisms

- How to Perform the Balance Beam Walk

- Benefits of the Balance Beam Walk

- Variations and Progressions

- How to Incorporate the Balance Beam Walk Into Your Training

- Programming Example: Coordination and Balance Circuit

- Scientific Insights

- Balance Beam Walk for Aging and Everyday Function

- Practical Tips for Implementation

- Summary

- References

The Balance Beam Walk is more than just a gymnastic skill—it’s a foundational exercise for improving stability, coordination, and overall motor skill. While it may look simple, walking along a narrow beam requires a remarkable blend of strength, sensory feedback, and precise neuromuscular coordination.

For athletes, adults in rehabilitation, or older adults working to maintain postural control, the Balance Beam Walk offers an effective way to enhance balance and proprioceptive awareness. Beyond its role in physical conditioning, it challenges the nervous system to integrate visual, vestibular, and somatosensory information—essential components of efficient and safe movement.

This guide explores the science, techniques, and progressions behind the Balance Beam Walk, and provides actionable training applications to help improve coordination and reduce injury risk.

What Is the Balance Beam Walk?

The Balance Beam Walk is a controlled locomotor exercise in which an individual walks heel-to-toe across a narrow beam, maintaining equilibrium and precision throughout the movement. The beam may be elevated (as in gymnastics), or at ground level for general fitness, physical therapy, or sports conditioning.

The exercise demands slow, deliberate movements that engage stabilizing muscles, enhance proprioceptive feedback, and train the brain to maintain postural control under challenging conditions.

In athletic performance, balance and coordination form the foundation for agility, spatial awareness, and injury prevention. This is why balance beam variations are often incorporated into neuromuscular training programs for sports like gymnastics, martial arts, football, skiing, and dance.

Muscles Worked

Although the Balance Beam Walk focuses primarily on coordination, several muscle groups play a crucial role in stabilization:

- Core muscles: rectus abdominis, obliques, erector spinae, and transverse abdominis maintain spinal alignment and prevent trunk sway.

- Hip stabilizers: gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae control lateral movement.

- Lower leg muscles: tibialis anterior, peroneals, and gastrocnemius help maintain ankle stability.

- Foot intrinsic muscles: provide micro-adjustments for balance.

- Shoulders and arms: act as counterbalances, aiding equilibrium during shifts in body weight.

Balance Mechanisms

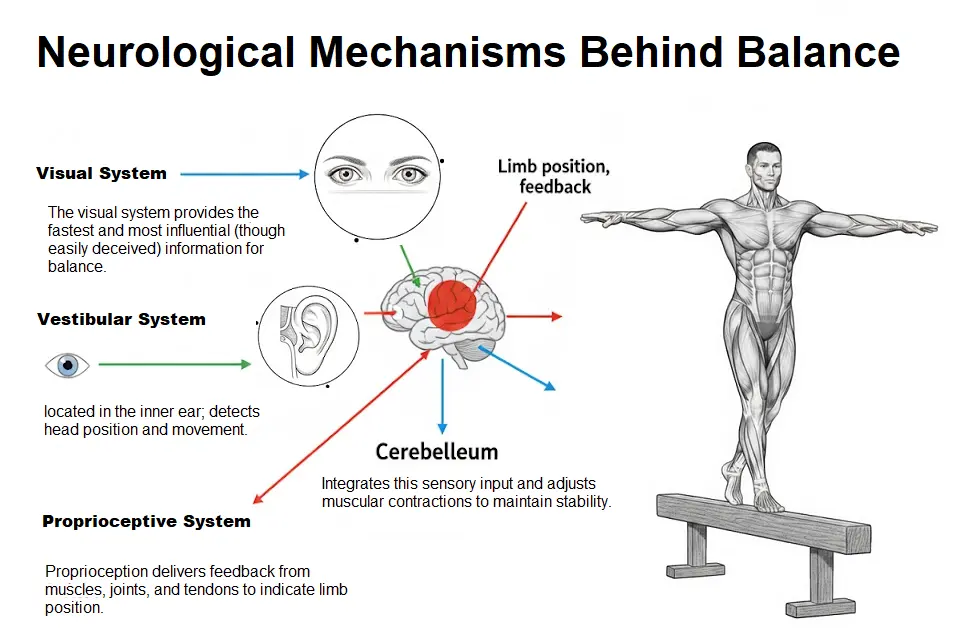

Balance and coordination rely on a network of sensory systems that continuously send feedback to the brain:

Visual system – provides environmental awareness and horizon orientation. The visual system provides the fastest and most influential (though easily deceived) information for balance. This is the main reason balance becomes challenging when the eyes are closed. The brain uses surrounding movement or stillness to infer whether the body is moving or not.

Vestibular system – located in the inner ear; detects head position and movement. Structures that detect the head’s position relative to gravity and linear acceleration. The vestibular system is the essential “internal gyroscope” that allows us to maintain balance even with our eyes closed.

Proprioceptive system – delivers feedback from muscles, joints, and tendons to indicate limb position. For example, this system allows you to touch your back without looking at your arms.

Cerebellum: It is the main balance control center that integrates all the information arriving from the three sensory systems and translates it into motor commands. The cerebellum compares this information with the current posture. When an imbalance is detected (e.g., an ankle roll), the cerebellum rapidly sends adjustment commands (contraction or relaxation) to the muscles to restore stability. These corrections occur automatically, without conscious thought. Damage to the cerebellum often results in unsteady gait (ataxia).

In summary, maintaining balance is a complex and automatic cycle involving sensing the environment (visual), head movement (vestibular), and limb position (proprioceptive), processing all this data in the cerebellum, and instantly executing the necessary muscle adjustments.

How to Perform the Balance Beam Walk

Step-by-Step Instructions

- Setup:

- Use a flat, stable beam or tape line on the floor (10–15 cm wide).

- Stand upright with your feet hip-width apart, eyes looking forward.

- Starting position:

- Extend your arms slightly to the sides for balance.

- Engage your core and maintain a neutral spine.

- Movement:

- Step forward slowly, placing one foot directly in front of the other (heel-to-toe).

- Keep your eyes fixed on the end of the beam—not your feet.

- Shift your weight smoothly with each step, avoiding jerky movements.

- Control and rhythm:

- Move slowly and maintain steady breathing.

- Focus on quiet, controlled foot placement.

- Completion:

- Once you reach the end, pause briefly before turning around and walking back.

Tips for Proper Form

- Keep your gaze forward—visual fixation aids balance.

- Avoid holding your breath; slow breathing stabilizes core tension.

- Use your arms as natural stabilizers, not rigid supports.

- Focus on precision rather than speed.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Looking down constantly, which can disrupt vestibular alignment.

- Taking steps too quickly or skipping heel-to-toe contact.

- Over-tensing the upper body, leading to instability.

- Neglecting proper posture (rounding shoulders or arching back).

Benefits of the Balance Beam Walk

1. Improved Postural Control

Walking along a narrow beam demands continual micro-adjustments, strengthening stabilizing muscles and teaching the body to maintain proper alignment during movement.

2. Enhanced Proprioception

Each step provides sensory feedback from the feet and ankles, improving body awareness and balance—key for both athletes and older adults.

3. Neuromuscular Coordination

The exercise reinforces communication between the central nervous system and muscles, refining motor unit recruitment patterns that enhance efficiency and precision.

4. Injury Prevention

Better balance and coordination translate to reduced fall risk and fewer non-contact injuries in sports or daily activities.

5. Rehabilitation and Recovery

The Balance Beam Walk is widely used in physical therapy to rebuild coordination after lower-limb or neurological injuries.

6. Cross-Training Benefits

Athletes in virtually any sport benefit from improved stability and movement control—critical for sprinting, landing, cutting, or rotating safely.

Variations and Progressions

Once you’ve mastered the standard Balance Beam Walk, you can add variations to further challenge balance and coordination:

1. Backward Beam Walk

Walk backward on the beam while maintaining visual focus ahead. Enhances proprioception and posterior chain activation.

2. Head Turns or Eyes Closed

Performing the exercise with head movements or closed eyes intensifies vestibular training by removing visual cues.

3. Single-Leg Pause Beam Walk

Pause for 2–3 seconds on one leg after each step to develop static balance control and strengthen the stabilizers.

4. Weighted Beam Walk

Hold a light medicine ball or wear a weighted vest to increase core demand and body awareness.

5. Dynamic Beam Walk (Sport-Specific)

Incorporate lateral steps, pivots, or arm movements to simulate athletic movement patterns and reactive control.

How to Incorporate the Balance Beam Walk Into Your Training

For Beginners

- Frequency: 2–3 sessions per week

- Duration: 3–4 sets of 30–45 seconds per walk

- Rest: 30 seconds between sets

For Athletes or Intermediate Level

- Frequency: 3–4 sessions per week

- Duration: 5–6 sets of 45–60 seconds

- Add instability (foam beam or soft surface) for increased challenge.

For Rehabilitation or Balance Training

- Focus on slow, deliberate movements with supervision.

- Use hand support or rails initially.

- Gradually decrease reliance on visual feedback.

For Sports Performance

Integrate the Balance Beam Walk as part of a neuromuscular warm-up circuit, pairing it with dynamic stability drills like single-leg hops, cone shuffles, or agility ladder work.

Programming Example: Coordination and Balance Circuit

| Exercise | Duration | Rest | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmer Walk | 15 sec | 20 sec | Postural control |

| Single-Leg Romanian Deadlift | 10 reps/leg | 30 sec | Dynamic stability |

| Walking Lunge | 15 sec | 30 sec | Balance and Coordination |

| Bulgarian split squat | 10 reps/side | 30 sec | Unilateral strength |

| Single Leg Broad Jump | 3 to 5 reps/side | 30 sec | Agility and foot coordination |

| Eyes-Closed Balance Hold | 20 sec | 30 sec | Vestibular adaptation |

Scientific Insights

Research indicates that balance and coordination training can significantly improve both neuromuscular control and cognitive processing. Studies show that engaging balance tasks activate brain regions responsible for spatial awareness, attention, and executive control.

For athletes, consistent balance practice leads to:

- Improved joint stability (especially ankle and knee)

- Faster reaction times

- Reduced injury risk

- Enhanced kinesthetic awareness

One study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (Paillard, 2017) demonstrated that 6 weeks of balance training improved single-leg stability and reduced ground contact time during sprinting—evidence of how postural control directly influences athletic efficiency.

Balance Beam Walk for Aging and Everyday Function

Balance isn’t just for athletes—it’s vital for aging adults too. As we age, sensory and neuromuscular systems decline, increasing fall risk. Balance beam drills help maintain gait stability, confidence, and spatial orientation.

Incorporating simple beam or line walks into a weekly routine can:

- Maintain lower limb strength

- Support cognitive-motor integration

- Prevent falls and enhance independence

Even brief sessions (10 minutes, 3 times weekly) can significantly improve dynamic balance in older populations, as shown in research from Clinical Interventions in Aging (2021). If you’re wondering how fit you are in your 50s, try these 5 simple strength tests

Practical Tips for Implementation

- Train barefoot or in minimalist shoes to enhance sensory feedback.

- Practice on different surfaces (foam, turf, or mat) to adapt proprioception.

- Focus on mindfulness—each step should be intentional and steady.

- Combine balance work with mobility drills for a complete movement foundation.

Summary

The Balance Beam Walk is one of the most accessible yet powerful exercises for improving balance, coordination, and neuromuscular control. Whether used for athletic performance, rehabilitation, or healthy aging, it develops the communication between mind and body that underpins all movement.

By integrating it regularly into your routine—with progressions, variations, and mindful execution—you’ll improve not only your stability but your total movement quality.

References

- Paillard, T. (2017). Plasticity of the postural function to sport and/or motor experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 72, 129–152.

- Behm, D. G., & Anderson, K. G. (2021). The role of balance training in athletic performance and injury prevention. Sports Medicine, 51(2), 217–230.

- Granacher, U., et al. (2010). Effects of balance training on postural sway, leg extensor strength, and jumping height in adolescents. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(4), 1228–1234.

- Shumway-Cook, A., & Woollacott, M. H. (2017). Motor Control: Translating Research into Clinical Practice (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Rogge, A.-K., et al. (2018). Balance training improves memory and spatial cognition in healthy adults. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 5661.

- Donath, L., et al. (2016). Effects of balance training on balance performance in healthy older adults: A systematic review. Sports Medicine, 46(9), 1293–1308.

- Horak, F. B. (2006). Postural orientation and equilibrium: What do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls? Age and Ageing, 35(2), ii7–ii11.

- World Health Organization (2021). Falls. WHO Fact Sheet.