Contents

If you’ve ever stepped into a gym, you’ve probably asked yourself: “Why do I need so many different exercises for the same muscle group? Can’t I just pick one and stick with it?”

At first glance, repeating a favorite exercise—like the bench press for chest or squats for legs—might seem enough. After all, if the target muscle is working, isn’t that all that matters?

The truth is more nuanced. Muscles are complex structures with multiple regions, fibers, and functions. Different exercises stress these areas in unique ways, leading to more balanced growth, injury prevention, and long-term progress.

Find out why you should change exercises for the same muscle group. We explain how this simple training tip leads to faster gains and a more balanced body.

Muscle Anatomy and Fiber Recruitment

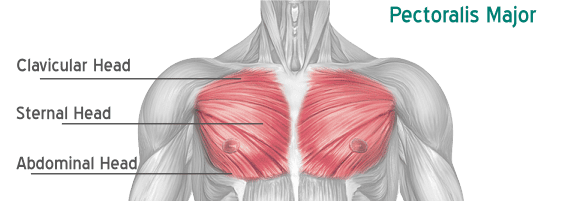

Muscles are not uniform blocks of tissue. Many have multiple “heads” or regions that respond differently depending on angle and movement. This is why relying on just one exercise—even if it “hits the muscle”—often leaves some regions underdeveloped.

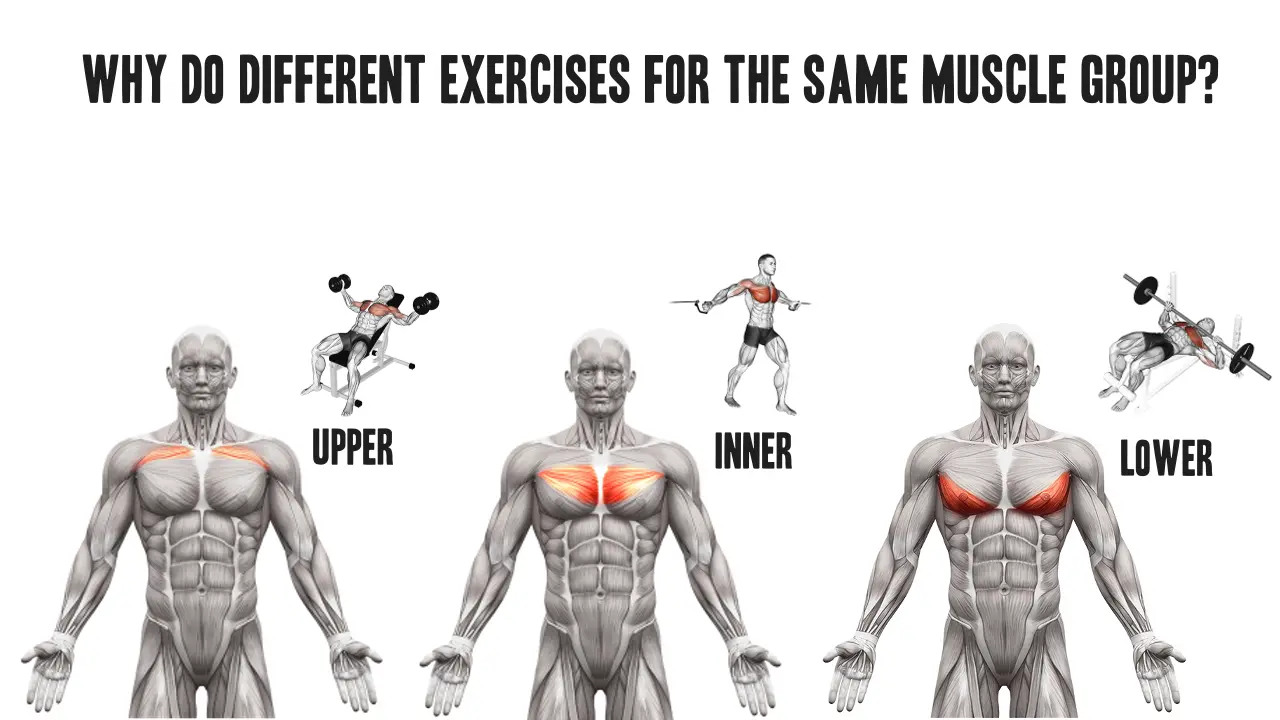

For Example Chest (Pectoralis major):

- Flat bench press emphasizes the sternal (middle) head.

- Incline bench press shifts focus to the clavicular (upper) head.

- Decline bench press activates the lower chest fibers for balanced development.

👉 If you only perform flat bench press, your chest may look strong in the mid-region but lack fullness in the upper chest, leading to an imbalanced appearance. By using different exercises, you ensure full development across the muscle, not just one section.

Range of Motion and Joint Mechanics

Every exercise moves a muscle through a unique range of motion (ROM). Some emphasize the stretch, while others target peak contraction.

- Romanian Deadlifts stretch the hamstrings under load.

- Leg Curls focus on contraction at the shortened position.

Why does this matter? Studies show that training muscles in both stretched and contracted states leads to greater hypertrophy than only one method. Variation ensures no part of the strength curve is neglected.

Neuromuscular Adaptation and Plateaus

Your body is remarkably adaptable. Perform the same exercise for weeks, and your nervous system becomes efficient at it—great for skill, but it limits growth stimulus.

- Early progress = nervous system adapting.

- Later stagnation = muscles no longer challenged.

By rotating exercises, you introduce novel stimuli, forcing the body to recruit fibers differently and preventing plateaus. This is why even advanced athletes change accessory lifts every few weeks.

Compound vs Isolation Exercises

Another reason for variation is the type of movement:

- Compound Exercises: Multi-joint lifts (e.g., squat, bench press, deadlift). They recruit large amounts of muscle mass, build overall strength, and stimulate hormones.

- Isolation Exercises: Single-joint lifts (e.g., bicep curl, tricep pushdown). They target weak points and allow precise muscle activation.

Compound lifts provide the foundation, while isolation ensures symmetry, weak-point correction, and full hypertrophy. 👉 Learn the pros and cons of both compound and isolation exercises

Injury Prevention and Longevity

Repeating the exact same exercise forever is not just boring—it can be harmful. Overuse injuries occur when the same joint pattern is stressed repeatedly.

- Example: Only bench pressing can overwork the shoulders.

- Adding dumbbell presses, push-ups, or cable flies changes loading patterns and protects joints.

Exercise variety also strengthens stabilizers (e.g., rotator cuff, core), reducing injury risk and improving athletic performance.

Scientific Evidence

Research strongly supports the role of variation in strength and hypertrophy.

- Fonseca et al. (2014): A 12-week study showed participants who varied lower-body exercises (squat, leg press, lunge) had greater overall muscle growth than those sticking to a single exercise.

- Schoenfeld et al. (2019): Demonstrated that exercise selection influences regional hypertrophy. Example: incline press promoted more upper chest growth than flat bench alone.

- Practical takeaway: Specific exercises matter. Different angles = different adaptations.

Practical Recommendations

How should you apply this knowledge? Here are evidence-based tips:

- Keep the Core Lifts Consistent

- Squat, bench press, deadlift, overhead press should remain staples.

- They provide measurable progress and foundation strength.

- Rotate Accessory Movements

- Change supporting lifts (e.g., lunges, fly variations, curls) every 4–8 weeks.

- This prevents plateaus and keeps training engaging.

- Train Through Different ROMs

- Combine stretched-position (e.g., RDLs, chest flies) and contracted-position (e.g., leg curls, cable crossovers).

- Balance Compound and Isolation

- Compounds build overall mass.

- Isolation fine-tunes symmetry and corrects weaknesses.

- Listen to Your Body

- Persistent pain = adjust exercise selection.

- Variety isn’t random—it should be strategic.

Conclusion

So, what’s the point in doing different exercises for the same muscle group?

- They target different fibers and regions.

- They stress muscles across the full range of motion.

- They prevent plateaus by introducing novel stimuli.

- They balance compound efficiency with isolation precision.

- They reduce injury risk and promote long-term training success.

In short: variety is not about doing “more” for the sake of it—it’s about doing different for smarter, healthier, and stronger results.

References

- Fonseca, R. M., Roschel, H., Tricoli, V., de Souza, E. O., Wilson, J. M., Laurentino, G. C., … Ugrinowitsch, C. (2014). Changes in exercises are more effective than in loading schemes to improve muscle strength. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(11), 3085–3092. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000539

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D., & Krieger, J. W. (2019). Effects of resistance training frequency on measures of muscle hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(10), 1557–1565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01184-9

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Physical activity. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity