Contents

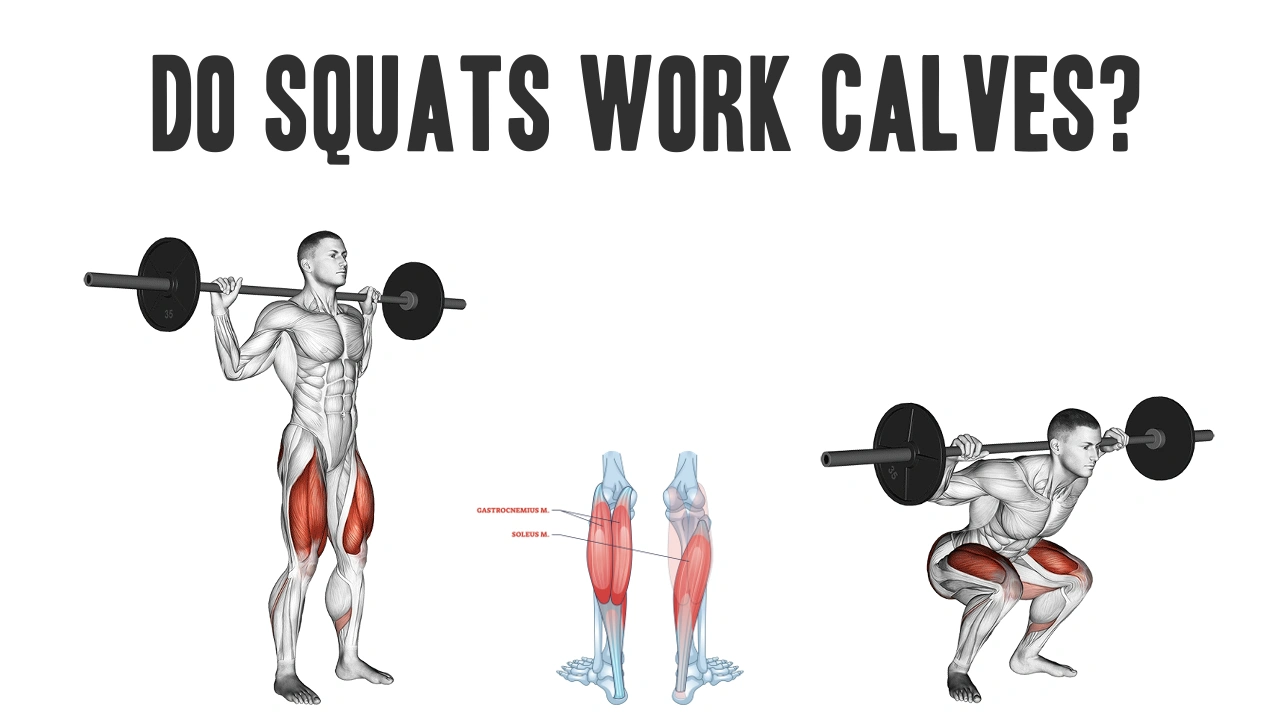

The squat is often hailed as the king of lower-body exercises—targeting major muscles like the quads, hamstrings, and glutes. But what about the calves? Many people overlook the role of the calf muscles during a squat. Do squats actually train them?

In this article, we’ll examine the anatomical function of the calves during the squat, which muscles are active, and how to better incorporate calf engagement into your training if needed.

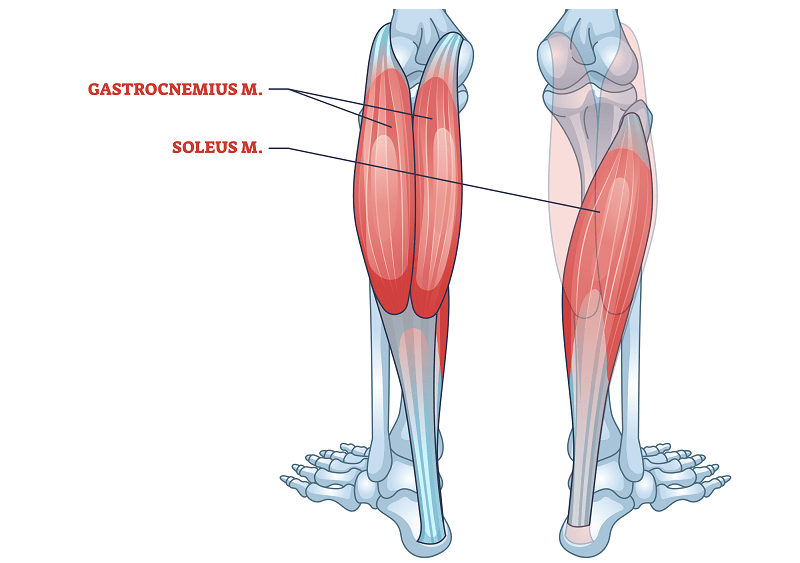

The Calf Muscles: A Brief Overview

The calf complex consists of two primary muscles:

- Gastrocnemius – The large, visible calf muscle that spans the knee and ankle joints.

- Soleus – A deeper muscle underneath the gastrocnemius that crosses only the ankle joint.

Together, these muscles control plantarflexion (pointing the foot down) and provide stability to the ankle during standing and dynamic movement.

Do Squats Work the Calves?

Short Answer: Yes, but indirectly and isometrically.

Here’s Why:

During a squat:

- The ankle joint remains relatively stable (especially in a standard back squat).

- The soleus is isometrically active to stabilize the ankle and help you maintain balance.

- The gastrocnemius, which crosses both the ankle and knee, has limited activation because the knees are bent throughout the movement.

Supporting Evidence:

EMG studies suggest that calf muscles are activated at low to moderate levels during squats—mostly to stabilize the body during the descent and ascent phases, not to drive the movement.

Key Study: Caterisano et al. (2002) showed that while quads, glutes, and hamstrings show high activation in a back squat, the gastrocnemius displayed low-level engagement, functioning primarily as a stabilizer, not a mover.

Calf Muscle Function During the Squat: Phase by Phase

1. Descent (Eccentric Phase):

- The body lowers by flexing the hips, knees, and ankles.

- The soleus contracts isometrically to maintain ankle stability and prevent dorsiflexion collapse.

- The gastrocnemius is largely inactive due to knee flexion reducing its tension.

2. Bottom Position:

- Ankle dorsiflexion peaks.

- The soleus remains active to stabilize the tibia.

- If wearing weightlifting shoes (heel-elevated), ankle mobility demands are reduced, slightly altering calf involvement.

3. Ascent (Concentric Phase):

- Hips and knees extend to stand upright.

- Soleus remains active, resisting backward ankle sway.

- Minimal dynamic contribution from the gastrocnemius unless performing a squat variation with ankle extension at the top.

How to Increase Calf Engagement in Squats

If you’re looking to engage the calf muscles more intentionally during lower-body training, consider the following methods:

1. Perform Squats with Heel Elevation

- Elevating the heels increases ankle plantarflexor demand.

- This may slightly increase soleus activation due to increased dorsiflexion range.

2. Add a Calf Raise at the Top

- Combine squats with calf raises to integrate concentric plantarflexion.

- Common in functional fitness or hypertrophy-focused training.

3. Use Tempo Squats

- Slower eccentrics and isometric pauses increase stability demands, promoting prolonged calf tension.

4. Try Front-Loaded Variations

- Goblet or front squats shift your center of gravity forward, demanding more ankle and calf stabilization.

Better Alternatives to Target the Calves Directly

While squats engage the calves to a small degree, they are not ideal for calf hypertrophy or strength. To directly target the calf muscles:

- Standing Calf Raises (targets gastrocnemius)

- Seated Calf Raises (emphasizes soleus)

- Donkey Calf Raises (stretch-emphasis for gastrocnemius)

- Loaded Jumping or Plyometrics (for explosive calf engagement)

Conclusion: Are Squats Enough for Calves?

Not quite. Squats do engage the calf muscles, but primarily for stability, not as prime movers. If you’re serious about developing your calves—whether for aesthetics, performance, or injury prevention—dedicated calf training should be a part of your program.

Still, squats are an essential part of any comprehensive lower-body routine, and their indirect activation of the calves contributes to overall ankle and knee joint integrity.

References

- Caterisano, A., Moss, R. F., Pellinger, T. K., Woodruff, K., Lewis, V. C., Booth, W., & Khadra, T. (2002). The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 16(3), 428–432.

- Escamilla, R. F. (2001). Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 33(1), 127–141.

- Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857–2872.

- Konrad, P., & Schmitz, K. (2008). Surface EMG studies of ankle joint stabilizers during squats and other functional tasks. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 18(6), 907–917. Link to abstract