Contents

The hamstrings are a group of three large muscles located at the posterior compartment of the thigh. They span both the hip and knee joints, playing a vital role in lower body movement, including walking, running, squatting, and stabilizing the pelvis. This article provides a science-backed breakdown of the hamstring group’s anatomy, biomechanics, common injuries, and training strategies to improve performance and minimize risk.

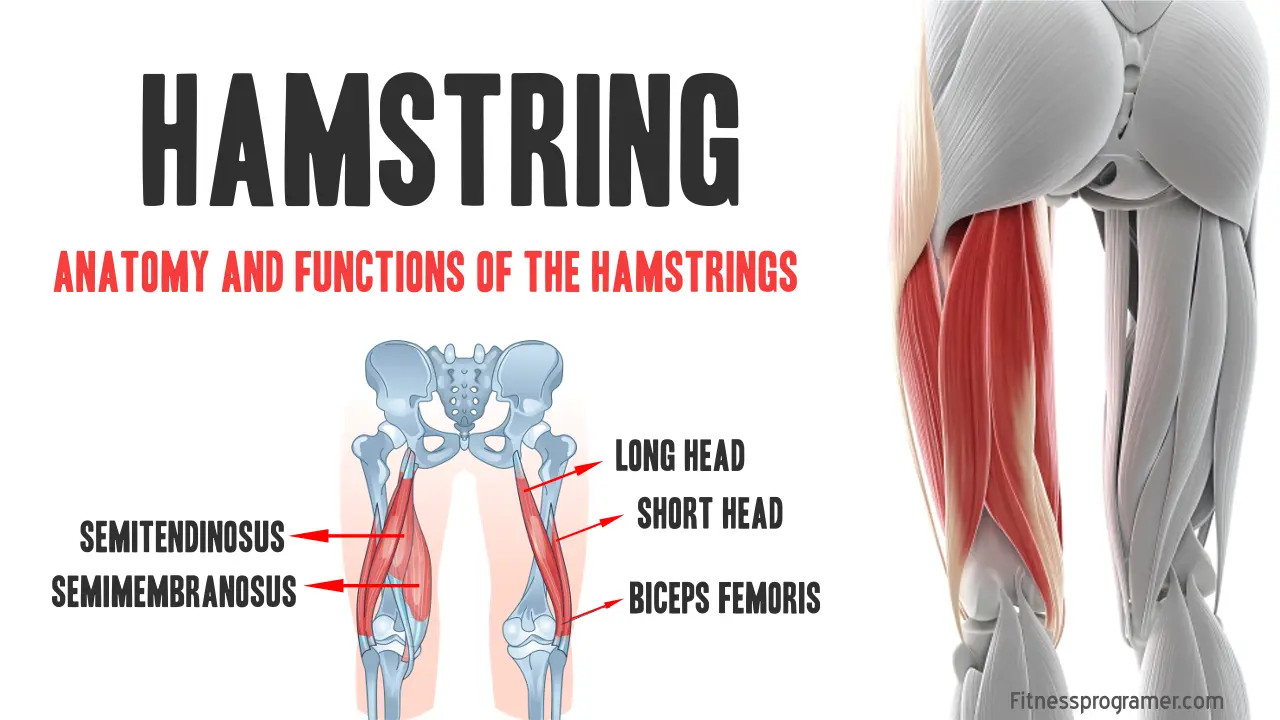

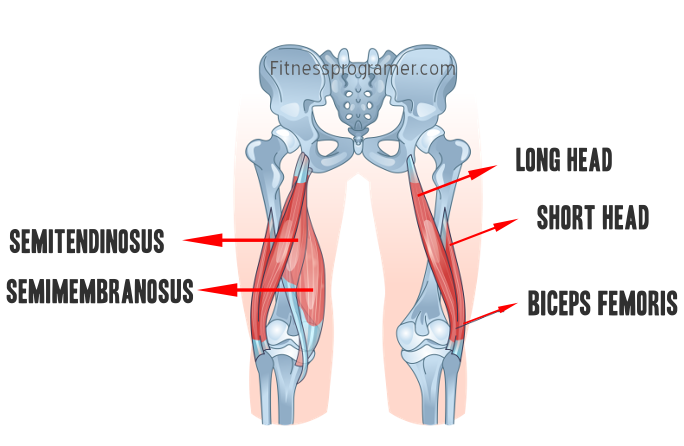

The Three Hamstring Muscles

The hamstring group consists of:

- Biceps Femoris (long and short head)

- Semitendinosus

- Semimembranosus

These muscles originate from the ischial tuberosity of the pelvis (except the short head of the biceps femoris, which originates on the femur) and insert below the knee on the tibia or fibula. They are biarticular muscles, meaning they cross both the hip and knee joints.

1. Biceps Femoris

- Long Head Origin: Ischial tuberosity (pelvis)

- Short Head Origin: Linea aspera of the femur

- Insertion: Head of the fibula

- Function:

- Knee flexion

- Lateral rotation of the leg when the knee is flexed

- Hip extension (long head only)

2. Semitendinosus

- Origin: Ischial tuberosity (pelvis)

- Insertion: Medial surface of the proximal tibia (part of the pes anserinus)

- Function:

- Knee flexion

- Medial rotation of the leg when the knee is flexed

- Hip extension

3. Semimembranosus

- Origin: Ischial tuberosity (pelvis)

- Insertion: Posterior surface of the medial tibial condyle

- Function:

- Knee flexion

- Medial rotation of the leg

- Hip extension

Functions of the Hamstrings Muscle Group

The hamstrings serve several key functions in locomotion and stability:

- Hip Extension: Vital for sprinting, jumping, and rising from a seated position.

- Knee Flexion: Required for running, squatting, and deceleration.

- Posterior Pelvic Tilt: Assists in stabilizing the pelvis and spine.

- Eccentric Control: During running, especially in the late swing phase, hamstrings decelerate the forward-moving tibia, preventing overextension.

How to Train the Hamstrings Effectively

A balanced hamstring program includes both:

- Hip-dominant exercises (targeting hip extension)

- Knee-dominant exercises (targeting knee flexion)

Top Compound Exercises:

- Romanian Deadlifts

- Kettlebell Swings

- Good Mornings

- DB Straight Leg Deadlift

- Hip Thrusts

- Stiff Leg Deadlift

- DB Pull Through

These engage the hamstrings along with glutes and other posterior chain muscles.

Top Isolation Exercises:

- Nordic Hamstring Curls

- Lying Leg Curls

- Seated Leg Curls

- Towel Leg Curl

- Stability Ball Leg Curls

- Banded Leg Curl

- Decline Dumbbell Leg Curl

Isolation exercises are ideal for muscle growth and correcting imbalances.

Volume and Intensity Guidelines

- Frequency: 2–3x per week

- Reps:

- Hypertrophy: 8–12 reps

- Strength: 3–6 reps

- Endurance: 12–20 reps

- Sets: 3–5 per exercise

- Rest: 60–120 seconds depending on goal

Training Tips

- Eccentric Emphasis: Incorporate exercises that focus on the lengthening phase to enhance muscle resilience.

- Glute Activation: Ensure the glutes are engaged to support hip extension movements.

- Unilateral Movements: Include single-leg exercises to address imbalances and improve stability.

- Form and Technique: Prioritize proper form to maximize effectiveness and reduce injury risk.

Muscle Activation Considerations

Exercises like Kettlebell Swings, Nordic Hamstring Curls and Romanian Deadlifts have been shown to elicit high levels of hamstring activation. Emphasizing a full range of motion and controlled eccentric phases can lead to significant strength and hypertrophy gains.

Hamstrings and Athletic Performance

Robust hamstring muscles are integral to various athletic endeavors:

- Sprinting: Facilitate powerful hip extension and knee flexion.

- Jumping: Contribute to explosive take-offs and controlled landings.

- Directional Changes: Aid in agility and quick transitions.

- Lifting: Support movements like deadlifts and squats by stabilizing the posterior chain.

Common Hamstring Injuries

Hamstring injuries are among the most common in sports. Understanding the types, causes, and risk factors is essential for prevention.

1. Strains (Pulled Hamstring)

- Grades:

- Grade I: Mild overstretching

- Grade II: Partial tear

- Grade III: Complete rupture

- Causes: Sudden acceleration or deceleration, insufficient warm-up, poor flexibility, muscle imbalances.

2. Tendinopathy

- Proximal hamstring tendinopathy (PHT) occurs at the ischial tuberosity and is common in runners and athletes with prolonged sitting or repetitive hip flexion.

3. Avulsion Injuries

- Occurs when the tendon pulls away from the bone, sometimes taking a piece of bone with it. Most common in adolescents and athletes under high force loads.

Risk Factors

- Previous hamstring injury

- Poor eccentric strength

- Fatigue and overtraining

- Muscle imbalances (e.g., quad dominance)

- Improper biomechanics

Prevention Tips:

- Progressive Overload: Gradually increase training intensity to allow adaptation.

- Dynamic Warm-Ups: Prepare the muscles for activity through movement-based stretching.

- Flexibility Training: Incorporate static and dynamic stretches to maintain muscle elasticity.

- Strengthening Exercises: Focus on both concentric and eccentric movements to build resilience.

When to Seek Medical Help

Seek professional evaluation if you experience:

- Sudden sharp pain in the back of the thigh

- Swelling, bruising, or inability to walk

- Chronic tenderness near the sit bone

- Recurrent strains despite proper training

Key Takeaways: Why the Hamstrings Matter

- The hamstrings play a critical role in lower body movement, stability, and athletic performance.

- Balanced training that includes both strength and flexibility components is essential.

- Preventative measures, including proper warm-ups and progressive training, can mitigate injury risks.

- Understanding the anatomy and function of the hamstrings can inform effective training and rehabilitation strategies.

References

- Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

- Opar DA, Williams MD, Shield AJ. Hamstring strain injuries: factors that lead to injury and re-injury. Sports Med. 2012;42(3):209-226.

- Bourne MN, et al. Effect of eccentric exercise on hamstring architecture. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(5):369–377.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Hamstring Injury Guide

- McCall A, et al. Risk factors, testing and prevention of hamstring injuries in professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(2):135–136.

- Biceps Femoris Activation during Hamstring Strength Exercises: A Systematic Review

- van Dyk, N., Behan, F.P., & Whiteley, R. (2019). Including the Nordic hamstring exercise in injury prevention programmes halves the rate of hamstring injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 8459 athletes. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(21), 1362–1370. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100045